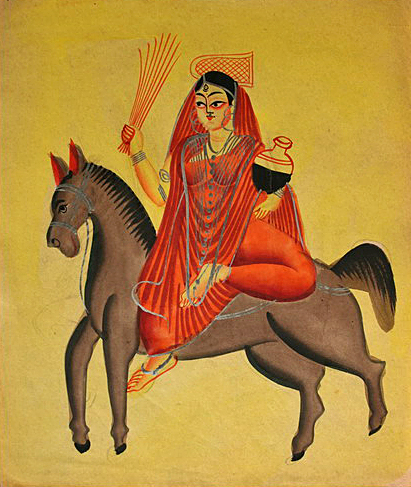

Śītalā-Saptamī

Today—the seventh day of the dark half of the lunar month of Bhādrapada—is Śītalā-Saptamī, a holiday dedicated to the goddess Śītalā, and celebrated primarily by Hindus with connections to North India, like myself (though, I’ll admit, I can’t say I remember ever celebrating it in my family).

According to Athavale in his book Saṃskṛti-Pūjana (1999, 5th ed., Gujarati)—or Dadaji, as he’s respectfully addressed by the followers of his Swadhyaya movement, like much of my family—the holiday is primary celebrated by women. On the day before the holiday (itself a holiday known as Rāndhana-Chaturthī, lit. ‘the sixth of cooking’), after cooking food enough for two days, women worship their cooking appliances and give them some much needed rest on the following day (lit. ‘the seventh of Śītalā’, the goddess of coolness) by eating cold food.

Of course, given the fact that the gendered nature of the holiday and its celebration are no longer appropriate in our context, we can say that it’s a holiday to be celebrated by and for those in the household responsible for cooking. I add the ‘for’, because in addition to being a day of rest for cooking appliances, it should also be a day of rest and appreciation for the cooks in the household. That I would say this is, of course, in no way tied to the fact that I’m the primary cook in our household (😉).

For Athavale (1999), the holiday is a day for women—or the cooks of the household, if we’re trying to be less gendered, as we should——to express their gratitude (kṛtajñatā) towards the tools of their trade—which of course sounds super problematic when gendered. It’s a day to acknowledge that these tools are valuable not only in the sense of being useful, but also in the sense of being sacred (pavitra), i.e., worthy of special respect and preservation.

I think there is much wisdom in cultivating this attitude of gratefulness, not only towards living beings but towards inanimate objects as well. The holiday provides a practical medium through which to put into practice what I take to be Dewey’s insight that nothing in this world is either a mere means or a mere end. Everything we experience is both a means and an end. To see everyday objects as sacred, to experience everyday life as imbued with the sacred, is a way to bring together the practical and aesthetic dimensions of lived experience in a really powerful way. I take this bringing together of the practical and the aesthetic to be a core feature of religious experience.

To see nature (prakṛtī)—i.e., everything that exists, including cooking appliances—as sacred, as brahman, is to see it as both a means and an end, to experience it in all its fullness, in both its practical and aesthetic dimensions, simultaneously. This is why I have come to believe that religious experience is neither solely concerned with moralizing, nor is it solely concerned with achieving some supposed final mystical beatitude. Religious experience is a way of living fully, involving both action (karma) and experience (jñāna).

This is why I now consider myself to be a bhedābheda-prakṛtī-brahmavādin or a bhedābheda empirical naturalist in the Deweyan sense, i.e., someone who believes that everything that exists is a real transformation (sat-pariṇāma) of nature (prakṛtī), that all these real transformations are at the same time both different (bheda) and non-different (abheda) from nature, and that everything that exists—nature (prakṛtī)—is brahman, is sacred, both a means and an end. Central to bhedābheda philosophy is the view that both action (karma) and experience (jñāna) are integral to living a good life. They are both central to religious experience.

Even cooking can be a religious experience. That is, in my view, the insight of this holiday. When you see the cooking appliances as more than mere means, they become sacred. The same goes for the cooks in one’s life. They are not mere means to your satisfaction. They’re whole persons and they should be appreciated in their wholeness.

Anyways, have a wonderful Śītalā-Saptamī!